Advocate Tawseef Manzoor Bhat contributed to this story.

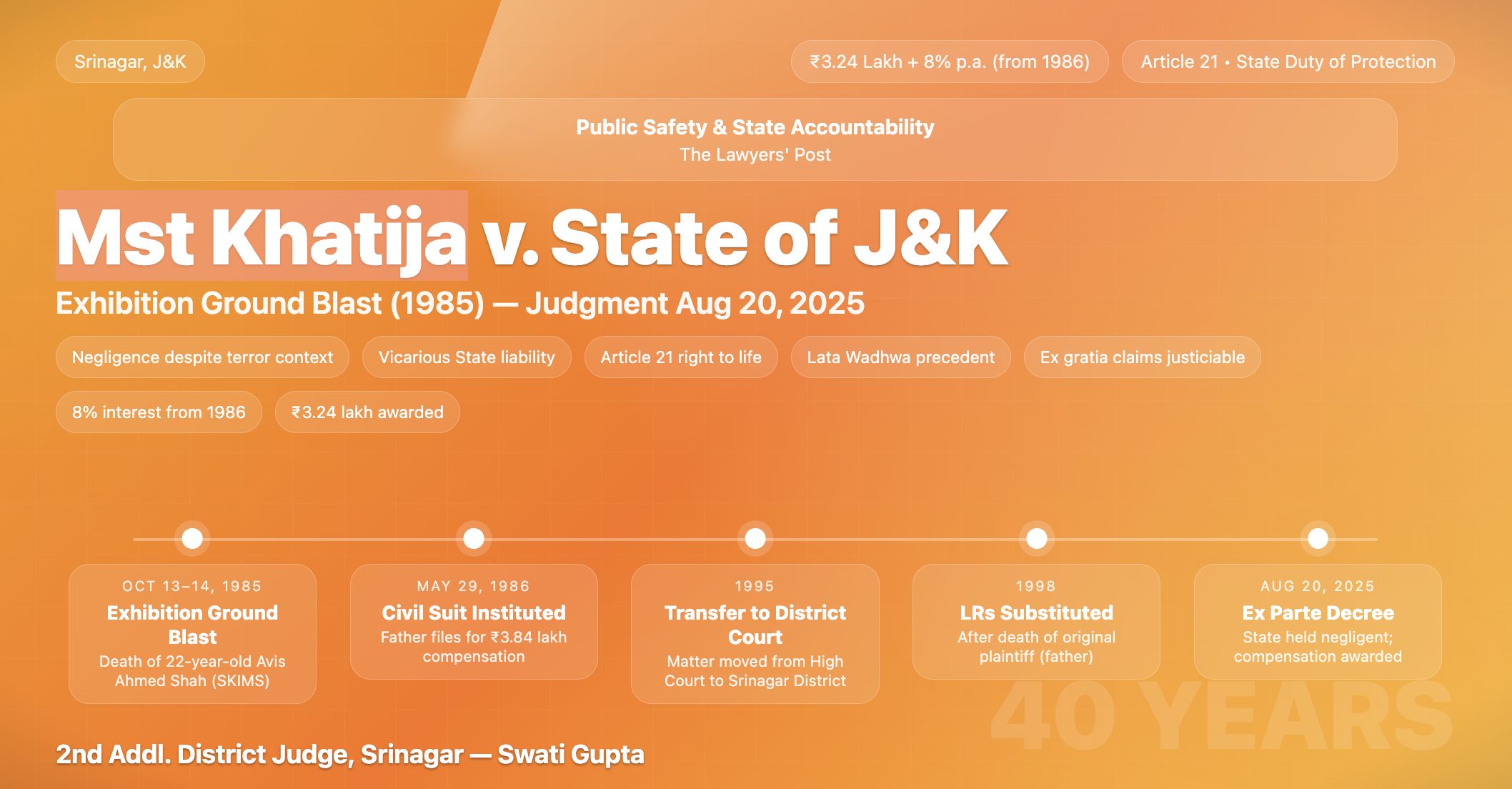

When 2nd Additional District Judge Swati Gupta delivered her judgment on August 20 in Srinagar, she brought closure to one of the Valley’s longest-running civil suits. The case, Mst Khatija v. State of J&K (Civil Suit No. 17/1995), had been pending for nearly four decades. Filed in 1986 and transferred to the district court in 1995, it concerned compensation for the death of a young man killed in the 1985 Exhibition Ground bomb blast. Judge Gupta’s order awarded his surviving family ₹3.24 lakh in compensation along with four decades of interest, holding the State liable for failing to ensure adequate safety at the government-run event.

On a chilly October evening in 1985, a 22-year-old mechanic named Avis Ahmed Shah bought a ticket to Srinagar’s annual trade fair and stepped inside a makeshift theater where music and dance performances drew crowds. Minutes later, a bomb detonated. Shah, struck in the head, was rushed to Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences. By morning, he was dead.

Nearly forty years later, a local court has finally ruled on the compensation claim filed by his father the following year. In a decision that underscores the grinding pace of civil justice in India — and the enduring question of the State’s responsibility for public safety during a time of terrorist violence — the 2nd Additional District Judge, Srinagar, awarded Shah’s family 3.24 lakh rupees plus decades of interest.

The case, Mst Khatija v. State of Jammu & Kashmir, is unusual even in Kashmir, where litigation often stretches for decades. It was instituted in 1986, transferred to the district court in 1995, and decided only this past week. The original plaintiff, Shah’s father, died in 1998. His widow and children carried on the case in his name.

When Mohammad Yousuf Shah filed his plaint in 1986, he asked for 3.84 lakh rupees, citing the wages his son earned as a mechanic — about 700 to 800 rupees a month — and his support for a household that included parents and unmarried siblings. His claim was grounded in a simple plea: the government had organized the exhibition, charged visitors for entry, and deployed police at the gates. The State, he argued, owed visitors a duty of care.

But the case moved slowly. It was transferred out of the High Court, relisted in Srinagar’s District Court, and repeatedly adjourned. After Shah’s death, his wife, Mst. Khatija, and their five children were substituted as plaintiffs. Meanwhile, the State’s appearances were sporadic; it was set ex parte on multiple occasions, only to have those orders lifted. By May of this year, when it failed to appear again, the court let the ex parte order stand.

By then, almost everyone connected with the original proceedings was gone. What remained was a brittle case file, witness statements recorded across the 1990s and 2000s, and a family still waiting for relief.

The facts of that October night are not in dispute. The government had set up stalls and amusements at the Exhibition Ground, a large open-air space in central Srinagar. Visitors bought tickets at the gate and, for certain attractions, purchased additional tickets. One of them was the Radha Theatre, a fenced-off arena for musical performances.

On October 13, 1985, as spectators gathered inside, an explosive device went off. Two men were injured. One of them was Avis Ahmed Shah. He died the next morning of severe head injuries and cerebral trauma.

Police registered an FIR. Investigators pointed to an underground terror outfit that called itself the “Holy War Fighters.” Several similar attacks had occurred before and after. In written submissions, the State argued that the exhibition had been properly secured, that all visitors were frisked, and that the tragedy was the result of terrorism beyond its control.

In its defense, the government of Jammu & Kashmir maintained that it could not be held liable for an act of terror. It acknowledged that it had organized the exhibition and charged admission but insisted that police had exercised due caution.

“The defendants… did not incur any liability for an incident beyond their control,” the State wrote in its 1998 statement. Security, it said, was adequate. The deaths were tragic, but not the result of negligence.

For decades, that line of defense held the case in limbo. No final ruling was issued. And as terrorism deepened in Kashmir in the late 1980s and 1990s, the political climate made the notion of State liability for terrorist violence all the more fraught.

Judge Swati Gupta’s ruling, issued August 20, takes a very different view. By charging fees and regulating entry, the State had created “an unspoken assurance of safety,” the court held. Once it undertook that responsibility, it could not disclaim liability when its security apparatus failed.

The judgment acknowledges the terror context but insists that it does not absolve the government of accountability. “If the law enforcement machinery makes a statement of such nature,” the court observed, referring to the State’s argument of helplessness, “it projects a picture of helplessness and ineffectiveness having the overall effect of erosion of the confidence of the general public.”

At its heart, the decision turns on constitutional law. Article 21 of India’s Constitution guarantees the right to life, and, the court said, when life is lost in a public space organized by the State, the violation cannot be brushed aside. The administration has a duty of restitution.

The court drew on the Supreme Court’s 2001 ruling in Lata Wadhwa v. State of Bihar, which emphasized the obligation of institutions and governments to provide relief to victims of mass tragedies. “Compensation therefore in such circumstances,” Judge Gupta wrote, “is not merely an act of restitution or a measure of providing damages but has to be given as a remedy intended to compensate the bereaved family enabling it to withstand the financial loss.”

The plaintiffs sought 3.84 lakh rupees. The court recalculated based on the deceased’s monthly wages, his age, and notional future income. It fixed compensation at 3.24 lakh rupees.

The more consequential part of the award lies in interest. The court granted 8 percent annual interest from 1986 — nearly four decades of accrual — and directed that the government pay within two months. If it fails, an additional 4 percent penalty will apply.

For a family long denied relief, the judgment transforms what might otherwise look like a modest figure into a significantly larger liability for the State.

The ruling matters for three reasons.

First, it reinforces the principle that governments cannot shrug off liability for violence at public events they organize. Even in the shadow of terrorism, the State owes a duty of care.

Second, it signals that ex gratia compensation for victims of terror is not purely an administrative matter. Courts can and will enforce claims as legal rights.

Third, it highlights the cost of delay. Interest running from the date of filing meant the State’s liability multiplied many times over. For the judiciary, it is a reminder that “justice delayed” can still carry financial teeth.

For decades, victims of terrorist violence and their families have struggled to obtain compensation, often caught between government relief schemes and legal hurdles. By grounding its award in Article 21, the court has effectively said: the right to life includes a right to accountability, and the State cannot hide behind conflict to deny it.

At the same time, the judgment is an indictment of India’s civil justice system. That a father’s claim, filed when Rajiv Gandhi was prime minister, should be resolved only after his death and long after his children had grown, is a stark example of how procedural delays hollow out remedies. The award of interest, while significant, does not erase the reality that the family lived without relief for four decades.

Finally, the case points to the evolution of Indian law itself. When it was filed, tort claims against the State were rare, and the jurisprudence of compensation under Article 21 was still emerging. Today, such claims are more firmly rooted. By applying contemporary principles to an old case, the Srinagar court has created a bridge across legal generations.

Whether the State will comply promptly with the judgment remains to be seen. But for lawyers and scholars, the ruling may prove influential in shaping claims for compensation in other contexts — from terror attacks to industrial disasters to police negligence.

“The exhibition ground is a public place where the general public is expected to visit under an unspoken assurance of safety,” Judge Gupta wrote. That line could reverberate in cases well beyond Kashmir.

For the family of Avis Ahmed Shah, the judgment brings a measure of closure, if not justice in full. Their son’s death was never in doubt. What remained in doubt for 40 years was whether the State bore responsibility. On August 20, 2025, a Srinagar courtroom finally said yes.